The most well known or popular example of the potential of propelling the super hero past this puerile pummeling or exploring them beneath their sometimes senseless hides is The Watchmen by Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons, which has had expanded exposure with the release of the recent film. Certainly this collection has earned its notoriety and popularity in its teenage transcendence or trek beyond the typical super-hero, yet there are other preceding and subsequent sequential collections that abound, although they are oft hid among the continual humdrum hoard that is accumulated out of a mostly abhorrently adolescent comic barrage.

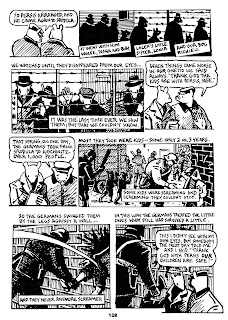

Outside of the massive amount of super-hero subject matter, (or intertwined within it), there are various other themes that have, and continue to inform and interest comic creators including crime, death, history, horror music, religion, sex, (to name but a few broad topics), all of which has been ongoing exponentially, particularly in titles drawn from real-life experiences, or that are autobiographical in nature. One of the most critically recognized of these self-aware titles is Maus; A Survivor's Tale by Art Spiegelman, which was awarded a Pulitzer Prize Special Award in 1992.

Therefore, one response to the continuation of pursuing comic books into adulthood would be to point out these exemplar explorations, that take a more literate consideration into these heroic graphic accounts, allow for a further or farther contemplation to the mature reader, and as such are worth the condemnation of 'uneducated' adults when they espy you unfolding these colorful or stark comic accounts and begin to snigger or sneer.

Thus is the intellectual involvement, and certainly it is worth noting or relating in ones defense of an adult comic continuance. Yet for me there is no denying that I have a love for the medium that continues, despite the disappointing deluge of predictable powers that still dominate the comic market in the United States, DC ,(Detective Comics), and Marvel, who continue to cater to the mass method of treating teenagers to predictable and prescribed super-hero procedures. DC, with their Vertigo line, intended for mature adults, has attempted to escape this tender trap, that comic books have wound up being mired or stuck in a prepubescent stage in America since the ‘witch hunts’ of Fredric Wertham in the 1950’s with his outrageous book Seduction of the Innocent, that nonsensically shut down EC (Entertaining Comics), and struck fear into the heart of every American comic book publisher with childish censoring decency codes.

Comic books in the U.S. survived this downfall, however since then have never completely recovered or shaken the stigma of being comic matter intended for adolescents. Elsewhere in the world, such as in Europe and Asia, the amalgam of image and word not only considers a wider audience, it allows a larger and more refined format to expand its subjects. Still in America, since the seventies there was a serious effort to shake or shuffle out of the strict code restricting comic books, mainly with one of the dominant companies DC, directing to depict real world issues, which were included in the Green Lantern/Green Arrow stories of Dennis O'Neal and Neal Adams. Then there was the underground comics movement with Robert Crumb influencing a multitude of future independent cartoonists, and setting the stage for subsequent self-realized subjects. The American comic boom of the 1980's created many offshoots outside of the big two, DC and Marvel, with serious RAW 'comic' efforts were imported to bring an awareness of the European graphic work to enlighten and entertain the more mature American comic reader. along with neglected sequential art in the states that explored subjects outside of the super-hero idiom.

Therefore despite the dual dominance of conglomerates DC and Marvel there are fortunately other options for the above average aged or non-traditional comic reader, (technically the super-hero genre is referred to as mainstream and other genres or subjects as non-mainstream). Dark Horse is one constant competitor that continues to challenge the expected limits of super-hero subject matter, and one could argue their growing presence was what birthed, (and continues to allow), DC’s Vertigo expansive experimentation. Image Comics occasionally contributes out-of-bounds of the super-hero formula, yet more importantly they allow the creator to own the rights to their work, (this in theory encourages more independence and creativity). ABC, (America’s Best Comics), is an imprint of Wildstorm Productions, that is now owned by DC, however at present remains separate editorially from its ‘parent’ company. Oni-press (which distances itself from super-hero subjects) and Top Shelf Comics are both publishers of alternative sequential stories that include a wide range of subject matter. One of the self-determining comic publishers has even adopted the name Alternative Comics as their named imprint.

Certainly today in America there are more independent comic publishers than in the past, since the collapse of the 1950’s with some die-hards resurrected from an untimely death such as Fantagraphics books, while other underground pioneers such as Kitchen Sink Press have perished (d.1999). Some individuals have even braved the self-publishing avenue and survived, such as Dave Sim (Cerebus-Aardvark-Vanaheim) and Jeff Smith (Bone-Cartoon Books). The largest self-publishing American success story was Kevin Eastman’s and Peter Laird’s Mirage Studios which exploded with the creation of their Teenage Mutant Turtles (today Nickelodeon owns all the rights to this creation, yet supposedly Mirage is allowed to publish 18 issues a year). Webcomics offer a further online alternative, and while I am not at all adverse to these efforts, (I am not a luddite or strict traditionalist), there is an acknowledged personal preference for the printed page, which will be my primary concern.

Involved in this ocean of American comics there are options abounding in Europe, (where the medium is more respected). Some of these graphic imports have become available in the states beginning with the early translations in Heavy Metal, (taken from the French Métal Hurlant), in 1977 and continuing in Art Spiegelman’s RAW, (1980-1991). Belgian born Herge’s /Georges Rémi, (1907–1983), Tintin series, which is of much changed dimensions from its original, yet still marvelous to behold. Jacques Tardi’s work (which has been featured in RAW), is due to be re-introduced by Fantagraphics with multiple translated stories of his highly influential graphic work. José Antonio Muñoz is an Argentine artist who has heavily influenced a number of American comic creators, (Frank Miller being the most well-known). Hugo Pratt is another comic creator, (from Italy), who has left his mark on Miller, and others in the U.S. Another eminent example of graphic storytelling is the series Blacksad created by Spanish authors Juan Díaz Canales ( writer) and Juanjo Guarnido (artist). Fortunately for English readers this series has been translated so that the story may be absorbed along with the astounding art.

The east has exerted tremendous influence on the American comic field with the import of Katsuhiro Otomo’s Akira in the U.S. in 1988 by Marvel Comics-Epic Comics, (recently re-published in 2000 by Dark Horse), and writer Kazuo Koike and artist Goseki Kojima’s Lone Wolf and Cub. These seminal sequential sagas defined manga, (literally whimsical pictures), and the latter in particular has had wide effects upon Western comics from Max Allan Collins’s Road to Perdition to Frank Miller’s Sin City. Another early imported Japanese innovator (who remains immensely influential) is Osamu Tezuka’s Astro Boy.

So the adult comic reader in America has a tidal amount of work to take in, from the past and present, and with this grand overview or cast into this sea my intent is to relate in more detail my past and ongoing experience with comics or the sequential storybook, and how it has influenced my own appreciation and affection for the medium. How in the best examples it transfers an immense possibility that is boundless as it is bounded by certain borders.

Primarily these series of relations will be based upon my understanding of the chronological medium as a reader, as opposed to practical experience as a comic creator. My own illustrative efforts have been more stilled, (and my writing for the most part outside of my drawing); although there is a desire to extend these single acts soon and set down my own sequential efforts, combining the two. While I do not claim to be a pundit in this field, (as compared to say Scott McCloud), there is an accumulated time frame where my perusal of panels have hopefully given me some insight to interest others, or instill in them not only knowledge, yet also the irresistible fondness that is drawn in and around comics, panel by panel.

An ongoing word and picture admirer,

E. Allen Smith

No comments:

Post a Comment